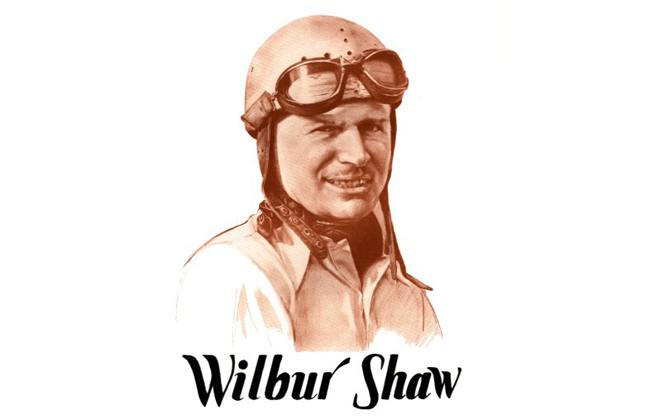

Class of 1991

Although Wilbur Shaw may be recognized as a great race driver in his own right, he is perhaps best known as the man who, with Tony Hulman, saved Indianapolis Motor Speedway from becoming an industrial park and helping to promote it into one of the world’s great motorsports facilities.

Shaw went to Indy races as a young man, where he idolized the great drivers of the time. He quit school to go to work with a storage battery company in Detroit. He was so adept at the job he soon was making $100 a week, a huge salary by 1919 standards.

Shaw went racing in 1921 in a car built of used or junked parts. It was at Hoosier Speedway and, at first, he was forbidden to drive because the starter felt he would kill himself in the makeshift racer. Shaw was so charming the starter helped him build a new car, which Shaw ran in 1922 and won repeatedly all over the Midwestern United States.

He continued racing and made it to Indy in 1927. He finished fourth, utilizing his hard-charging driving style. He continued to race through the years, making a fair living driving other people’s cars.

But in 1936, he encountered the turning point of his career. He returned to Indy as the major owner of his own car. He placed seventh in that year, but the next year, he won the vaunted race. In that same year, he raced in Europe, becoming the first spark to unite Americans and Europeans at Indianapolis. He convinced a Chicago industrialist to sponsor a Maserati at Indy and, as one might expect, Shaw won with it in 1939 and 1940. By World War II, Shaw had given up all forms of racing but Indy. During the war, he worked as an aviation sales manager for Firestone, but the routine work nearly drove him crazy. This may have sparked his interest in saving Indy, which was in decline after Eddie Rickenbacker had lost interest and tried to convert it into an industrial park.

With Hulman’s help, Shaw struggled to put on the 1946 race. The race was a success and Indy was saved.

The dapper Shaw was the ideal man to represent racing to automobile executives, whose cooperation Shaw realized was sorely needed. His efforts spurred the growth of auto racing in the United States, and he was still hard at it when he lost his life in a private plane crash.

Today, a rest stop on the Indiana Turnpike is named after him. He is honored along with Knute Rockne, poet James Whitcomb Riley and several governors. It is only fitting. His memorial might be one for a school dropout, bracketed by poets, college men and governors, but for those who today enjoy the fruits of his labors in motorsports, that is exactly where it should be.